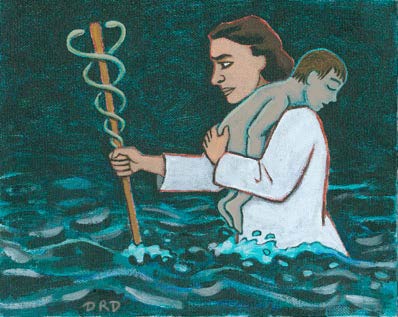

I was in the middle of discharging a five-year-old who had taken a toxic dose of the tricyclic antidepressants his mother had left out on her nightstand, when I got a page from the emergency room. They needed an intensive care bed for a 15-month-old near-drowning victim. I winced when I heard the diagnosis. For the general public, “near drowning” evokes images of a lifeless victim who miraculously comes back to life after water is pumped out of his or her lungs by a heroic bystander. I know better: near-downing victims often are kept alive by heroic medicine.

After I got off the phone, I finished talking to the mother of the five-year-old about keeping drugs and poisons out of the way and preferably locked up. My talk stressed the obvious, but I know hospitalization can be a strong motivator when it comes to parents changing their ways, so I always try to take advantage of the opportunity.

The emergency room sent Christopher Agostini to the unit wrapped in a blanket, wearing only a diaper and a necklace. Christopher had been playing in the backyard, and his father had found him facedown in a kiddie pool no more than ten minutes after he had told him to get away from the water. Now, the toddler was intubated and needed a respirator to breathe. A computed tomography scan of his head showed diffuse brain swelling.

While we waited for Christopher’s parents to drop their other children off with family and drive to the hospital, we began integrating him into our lives on the unit. Christopher’s nurse, Elaine, calibrated the arterial line that measures blood pressure through an artery in his wrist. After she had tended to the technical aspects of nursing, she wiped his face and combed out his wavy brown hair. Then she removed the medal from around his neck, and in a flash of gold, I saw a familiar depiction of aman carrying a child through water—Saint Christopher, of course. Elaine put the medal in a clean urine cup for safekeeping.

When Christopher’s parents arrived, we gave them a brief medical update, and then Elaine explained the tubes and wires. His mother didn’t tear up until Elaine handed her the medal. There’s plenty to cry about in the ICU, but, strangely, most parents save their tears for elsewhere. Mrs. Agostini dried her eyes and fingered the medal. “I want him to wear this,” she said.

“I took it off for safekeeping. I’d hate to see it get lost,” Elaine explained.

“We’ll take that chance,” said Mr. Agostini, who held his son’s hand while Elaine replaced the necklace.

Dr. Reynolds, the attending, shepherded the parents to the conference room. He was going to hang the crepe—the physician’s term for preparing the family for a bad outcome. Expectations are high in the ICU. Parents hear miraculous stories on the news almost nightly. Indeed, the news vans regularly park right out front to report our successes with transplants and with stereotactic surgeries to remove discrete areas of seizure-prone brain tissue. The vans come also to feed on sadness: a police officer who dies in our emergency room; a child shot by his mother’s boyfriend.

I knew Dr. Reynolds wouldn’t sugarcoat if for Christopher’s parents. He would explain that the brain can live only a short time without oxygen, and from the looks of Christopher’s CT scan, there was widespread brain damage. His neurological exam, with fixed and dilated pupils and clenched hands, reflected this damage.

While there are amazing stories of recovery after prolonged submersion, these usually involve people who have drowned incold water, which rapidly cools the victim and slows the body’s metabolism and, subsequently, the rate of damage. But Christopher was young, and the brain has amazing recuperative powers, so we did everything in our power to keep him alive.

Huddled together and wiping away the tears, the Agostinis wouldn’t hear anything about the limits of our powers. They told Dr. Reynolds they were sure God would cure their son. To me, the ICU—with its shaken babies and first-graders with brain tumors—seemed far from God’s loving care. But I wasn’t angry with God; I was angry with the parents who left their toddler alone with a pool of water.

Over the days, Christopher’s bed became a shrine. Holy cards appeared: the Virgin Mary, guardian angels, Saint Jude (the patron saint of impossible causes), and, of course, Saint Christopher. His mother pinned relics to his pillow and hung a small cross made of blessed palm over his bed.

I could smell the faint scent of dried palm every time I stood at the head of the bed and retaped the endotracheal tube. Christopher was an easy ICU patient. He phenobarbital sedated him and reduced his seizures to two or three a day. By the second week, however, his brain had recovered enough for him to become agitated and pull at his intravenous lines and the nasogastric tube that fed him.

Mrs. Agostini saw this activity as a sign of his improvement, and she complained bitterly when the nurses sedated him. We explained that when Christopher thrashed around, he could pull out the central lines that were tucked deep inside blood vessels close to his heart. The endotracheal tube kept him breathing, but if he worked against the ventilator, the tiny, grape-like balloons in his lungs could pop.

We doctors quietly hoped for a miracle, just as Christopher’s parents did. There are anecdotal reports in the medical literature of children making good recoveries after being pulseless longer than Christopher had been. But another week passed, and he had improved very little.

We could not keep the breathing tube in his trachea much longer, or there would be damage. And if we couldn’t get him off the ventilator, he would need a tracheostomy. Slowly, we started to wean him off the ventilator. Early on a Sunday morning, we assembled after rounds to remove the endotracheal tube, giving Christopher a chance to breathe on his own.

“Christopher,” I said, as I checked the laryngoscope in case we needed to reintubate him, “you have to breathe when we take the tube out, okay?” I patted his shoulder and saw the medallion glitter in the overhead light. As he let out a deep breath, I pulled out the tube and held my breath. He breathed; I breathed. Deep down in the most primitive area of his brain, enough had been spared. I left the laryngoscope at the bedside for the rest of the morning, and eventually I put it away.

It wasn’t until a few days later than Christopher opened his eyes. He didn’t recognize his parents, and when we dangled a toy in front of him, his eyes didn’t follow it. The only times his arms and legs moved were during his seizures, which were down to once a day. He made garbled noises when he was agitated. He didn’t point to things he wanted. Mrs. Agostini started thinking preschool; I started arranging his transfer to a pediatric rehabilitation center.

I could understand just a small part of his parents’ pain. They had to live with the fact that their once-perfect son has been lost in the accident. They would have to mourn the Christopher they had lost and accept the Christopher they now held. This would be a long process—one that some parentsnever finish. They also had to face the fact that although medicine seems miraculous, doctors are sometimes more comfortable acknowledging their limits. It isn’t that we lack hope. We try. We try very hard. But unlike Saint Christopher, we cannot carry every child safely across.

The Agostini family, I knew, would wait patiently for a miracle. Their lives had been changed forever. Christopher needed daily physical therapy so that the stronger flexor muscles didn’t overpower the weaker extensors and curl him into a tight ball. When he got a cold, he’d need suctioning because his swallowing and gag reflexes were not entirely normal. He’d take time away from his siblings and limit things like vacations and changing health insurance. He had returned to being a two- month-old baby, forever dependent on his parents.

After three weeks in the ICU, Christopher was ready to leave. An ambulance came to transport him across town to the children’s rehabilitation center. There was no need to review water safely with Mr. and Mrs. Agostini; Christopher would never be able to put himself at risk again. I signed my name to the transport order and said goodbye. Elaine had tucked Christopher’s medallion under his gown and two layers of blankets. Saint Christopher, after all, is the patron saint of travelers, and Christopher had a long road ahead of him.